“More” is the operative word for this report on school book bans, which offers the first comprehensive look at banned books throughout the 2021–22 school year. This report offers an update on the count in PEN America’s previous report, Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights (April 2022), which covered the first nine months of the school year (July 2021 to March 2022). It also sheds light on the role of organized efforts to drive many of the bans.

Many Americans may conceive of challenges to books in schools in terms of reactive parents, or those simply concerned after thumbing through a paperback in their child’s knapsack or hearing a surprising question about a novel raised by their child at the dinner table. However, the large majority of book bans underway today are not spontaneous, organic expressions of citizen concern. Rather, they reflect the work of a growing number of advocacy organizations that have made demanding censorship of certain books and ideas in schools part of their mission.

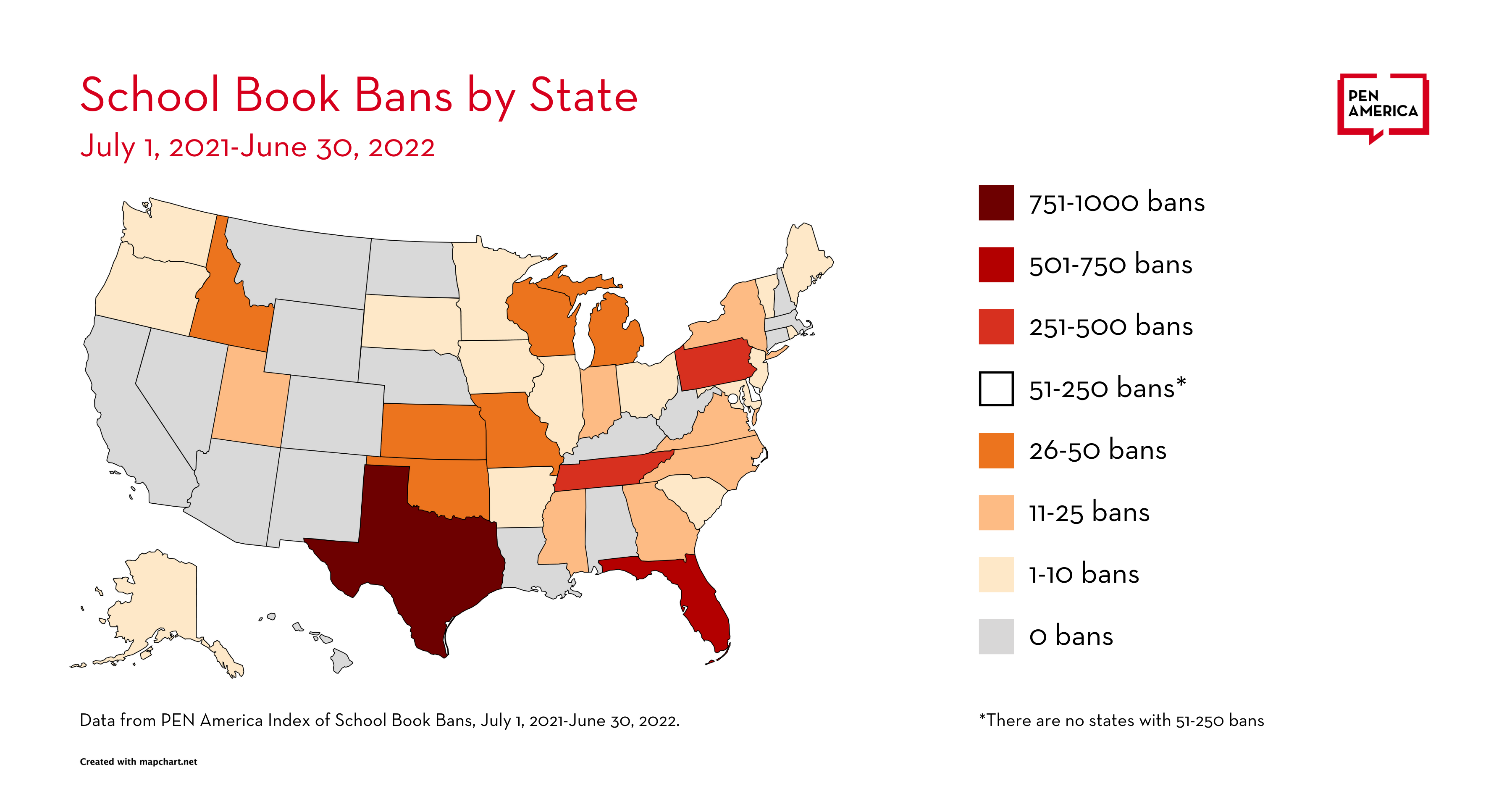

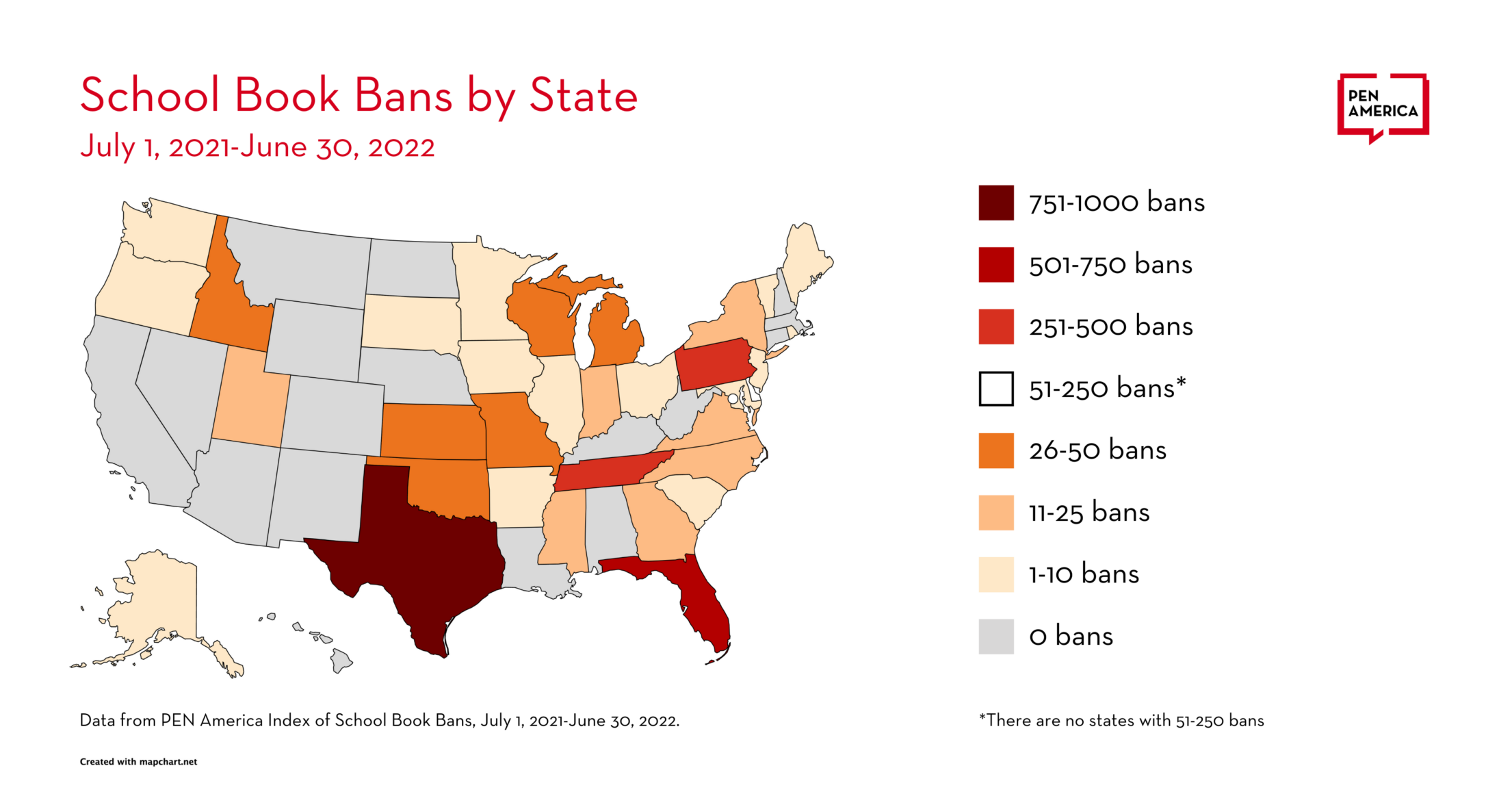

The numbers in this report represent documented cases of book bans reported directly to PEN America and/or covered in the media; there are likely additional bans that have not been reported. 1 In August, the Houston Chronicle released a report on the partisan nature of book bans in Texas between 2018 and 2021. The newspaper reported finding more than 1,000 bans in Texas during that time frame, which overlaps only in part with the time period covered by this report. That data was not available to review for inclusion in this report in advance of publication.

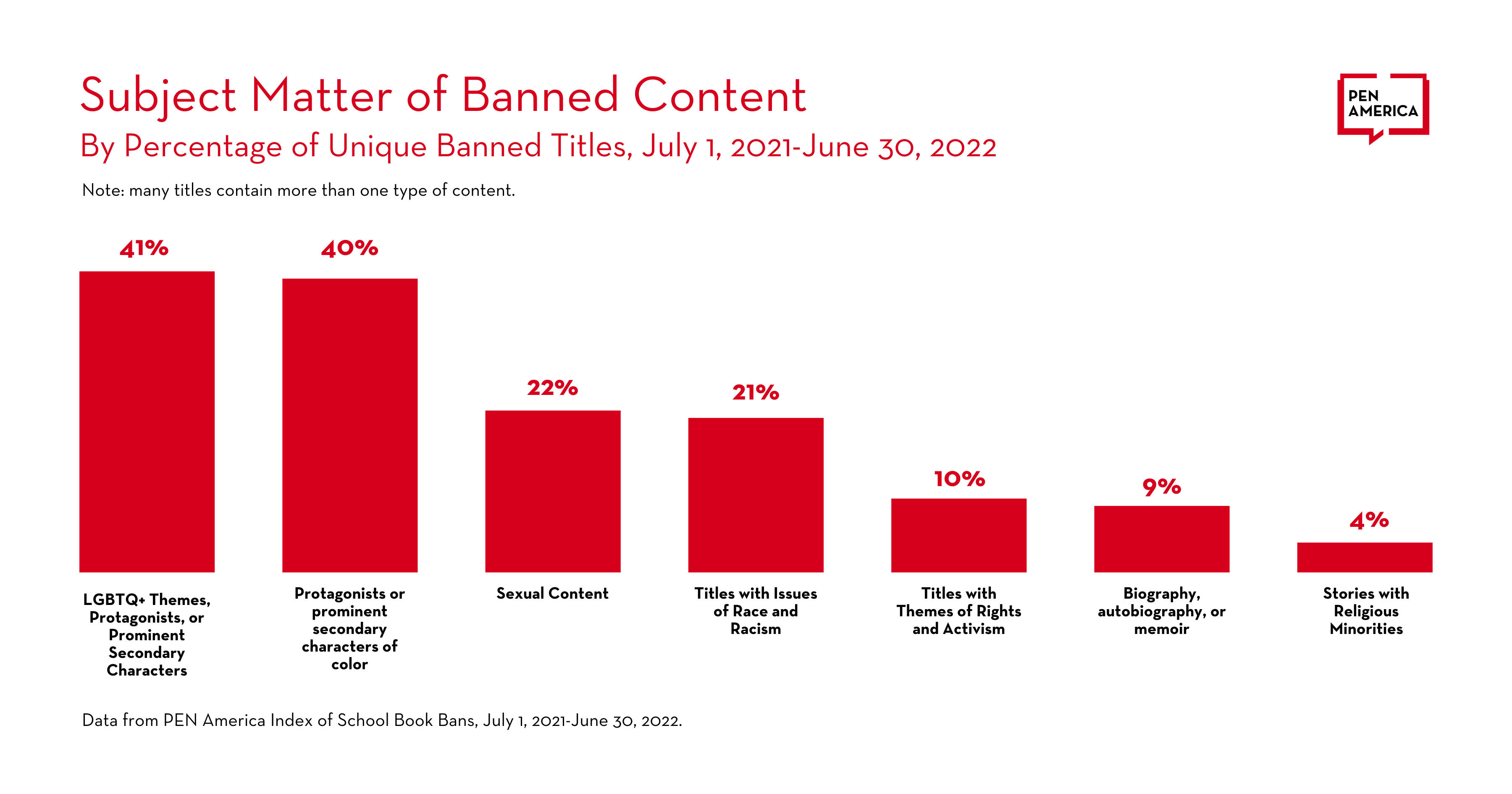

Over the 2021–22 school year, what started as modest school-level activity to challenge and remove books in schools grew into a full-fledged social and political movement, powered by local, state, and national groups. The vast majority of the books targeted by these groups for removal feature LGBTQ+ characters or characters of color, and/or cover race and racism in American history, LGBTQ+ identities, or sex education.

This movement to ban books is deeply undemocratic, in that it often seeks to impose restrictions on all students and families based on the preferences of those calling for the bans and notwithstanding polls that consistently show that Americans of all political persuasions oppose book bans. And it is having multifaceted, harmful impacts: on students who have a right to access a diverse range of stories and perspectives, and especially on those from historically marginalized backgrounds who are watching their library shelves emptied of books that reflect and speak to them; on educators and librarians who are operating in some states in an increasingly punitive and surveillance-oriented environment with a chilling effect on teaching and learning; on the authors whose works are being targeted; and on parents who want to raise students in schools that remain open to curiosity, discovery, and the freedom to read.

PEN America has identified at least 50 groups involved in pushing for book bans at the national, state, or local levels. This includes eight groups that have among them at least 300 local or regional chapters. PEN America has identified these chapters based on the national groups’ own listings, by chapter or regional websites, and by their official chapter and regional group pages on Facebook. Insofar as we have been able to establish, there are at least another 38 state, regional, or community groups that do not appear to have formal affiliations with national organizations or with one another.

These groups share lists of books to challenge, and they employ tactics such as swarming school board meetings, demanding newfangled rating systems for libraries, using inflammatory language about “grooming” and “pornography,” and even filing criminal complaints against school officials, teachers, and librarians. The majority of these groups appear to have formed in 2021, and many of the banned books counted by PEN America can be linked in some way to their activities. Some of the groups espouse Christian nationalist political views, while many have mission statements oriented toward reforming public schools, in some cases to offer more religious education. In at least a few documented cases (for example, in Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania), the individuals lodging complaints about books did not have children attending public schools when at the time they raised objections.

This evolving censorship movement has grown in size and routinely finds new targets and tactics, homing in on the books encompassed in district book purchases or digital library apps. A parallel but connected movement is also targeting public libraries, with calls to ban books; efforts to intimidate, harass, or fire librarians; and even attempts to suspend or defund entire libraries.

PEN America defines a school book ban as any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished.

It is important to recognize that books available in schools, whether in a school or classroom library, or as part of a curriculum, were selected by librarians and educators as part of the educational offerings to students. Book bans occur when those choices are overridden by school boards, administrators, teachers, or even politicians, on the basis of a particular book’s content.

School book bans take varied forms, and can include prohibitions on books in libraries or classrooms, as well as a range of other restrictions, some of which may be temporary. Book removals that follow established processes may still improperly target books on the basis of content pertaining to race, gender, or sexual orientation, invoking concerns of equal protection in education. For more details, please see the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022).

Since PEN America published our initial Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights (April 2022) report, tracking 1,586 book bans during the nine-month period from July 2021 to March 2022, details about 671 additional banned books during that period have come to light. A further 275 more banned books followed from April through June, bringing the total for the 2021-22 school year to 2,532 bans. This book-banning effort is continuing as the 2022–23 school year begins too, with at least 139 additional bans taking effect since July 2022.

In addition to the role played in book banning by local, state, and national groups, efforts to restrict access to books were also advanced in the past year by government officials and enabled by both state-level legislation and district-level policy changes. PEN America estimates that at least 40 percent of the bans counted in the Index of School Book Bans for the 2021–22 school year are connected to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers. Some officials for example sent letters specifically inquiring into the availability of certain books in schools, such as occurred in Texas, Wisconsin, and South Carolina.

Since March 2022, we have also seen for the first time educational gag orders passed that implicate restrictions on books, most notably in Florida, as well as a range of other new laws that have put pressure on schools to censor their libraries. The Alpine School District in Utah responded to a new law, HB 374 (“Sensitive Materials in Schools”), by announcing the removal of 52 titles in July, but then opted to keep the books on shelves with some restrictions after national pushback. In August, some school districts in St. Louis, Missouri began to pull books from shelves in response to a law that made it a class A misdemeanor to provide visually explicit sexual material to students. These trends are unfortunately likely to continue, as the chilling effect of these legislative measures spreads.

Altogether, this report paints a deeply concerning picture for access to literature, and diverse literature in particular, in schools in the coming school year. Book banning and educational gag orders are two fronts in an all-out war on education and the open discussion and debate of ideas in America. Students have First Amendment rights to access information and ideas in schools, and these bans and legislative shifts pose clear threats to those rights. This climate is also increasingly undermining the professional discretion of educators and librarians when it comes to matters of public education, and disrupting the potential for effective relationships between parents, teachers and administrators that can actually serve to advance student learning and civic engagement.

Students retain their First Amendment rights in schools. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a 1969 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Thirteen years later, in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, the Court noted the “special characteristics” of the school library, making it “especially appropriate for the recognition of the First Amendment rights of students,” including the right to access information and ideas.

What does this mean for districts who receive a request to reconsider a library holding?

Legal precedent and expert best practices demand that committee members, and principals, superintendents, and school boards act with the constitutional rights of students in mind, and using established processes, cognizant of the harm in eliminating access for all based on the concerns of any individual or faction.

What if a book is obscene?

The term “obscenity” holds particular meaning in the legal sense. Obscene material is not protected under the First Amendment, but a finding of obscenity requires satisfaction of a tripartite test, which requires, among other aspects, a holistic consideration of the material at issue. Simply declaring a book “obscene” does not make it so.

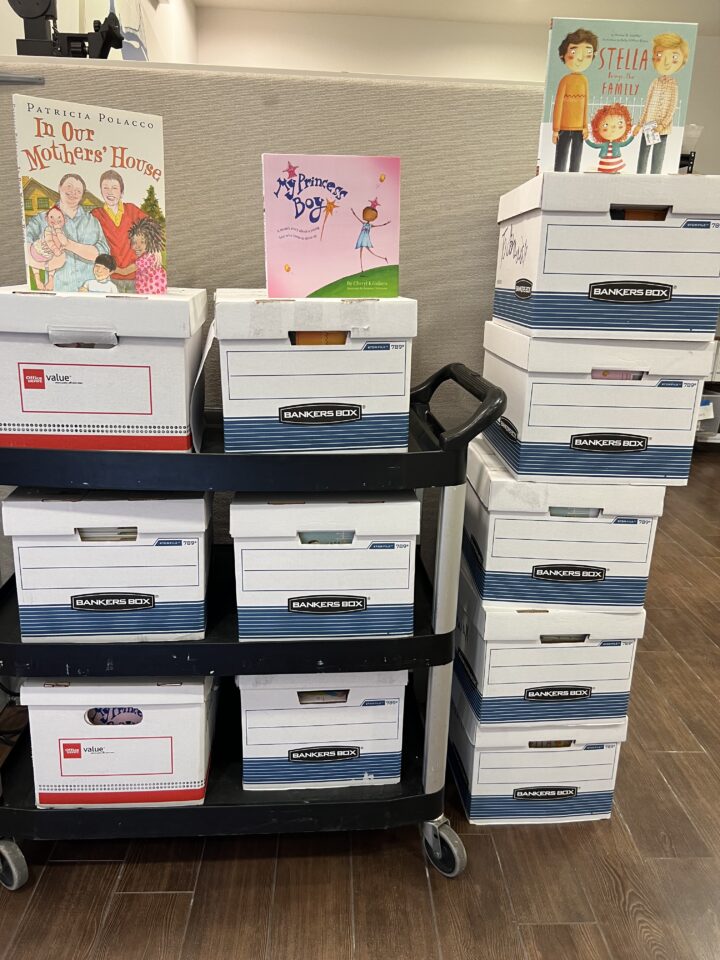

Broward County, Florida, public schools donated 11 boxes of LGBTQ+-themed books to the Stonewall National Museum & Archives a week before the state’s “Parental Rights in Education” law—also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law—took effect. The district said it was removing the books to clear office space.

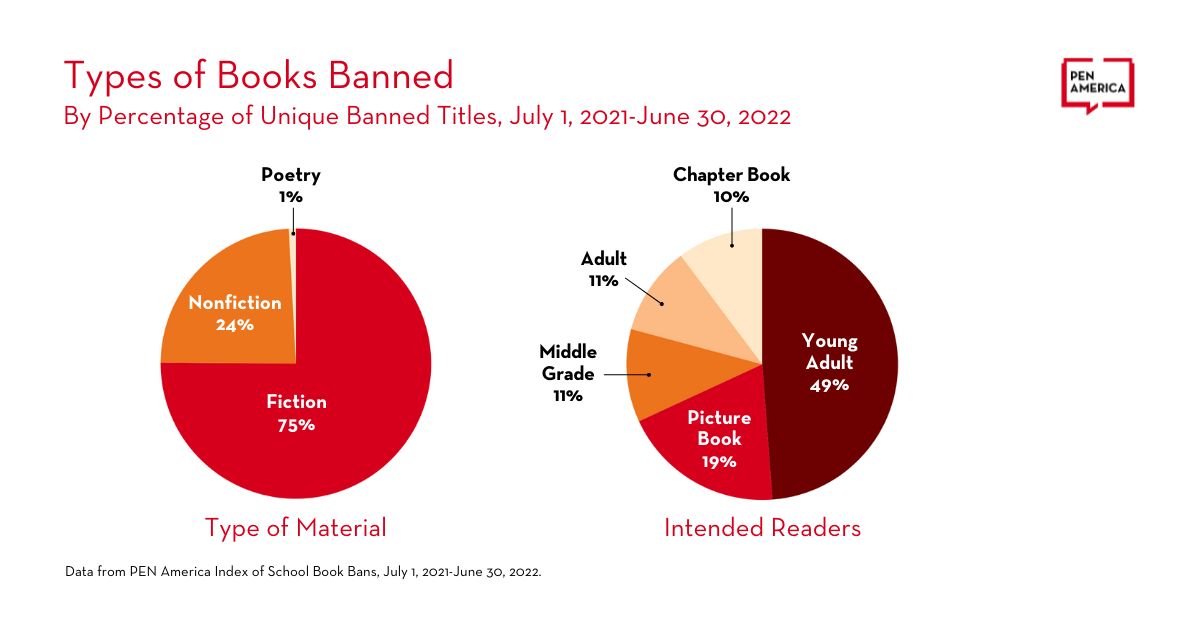

Complaints about diversity and inclusion efforts have accompanied calls to remove books with protagonists of color, and numerous banned books have been targeted for simply featuring LGBTQ+ characters. Nonfiction histories of civil rights movements and biographies of people of color have been swept up in these campaigns. For example, many volumes in the popular Who Was? chapter book series and several biographies of Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor were banned in Central York School District in Pennsylvania. That ban also impacted hundreds of books with protagonists of color, including the Caldecott Honor–winning A Big Mooncake for Little Star. In a similar example, Duval County Public Schools in Florida opted not to distribute sets of the Essential Voices Classroom Libraries collection of books after they had been purchased, flagged for concern over their content. This collection of 176 unique titles has been effectively banned from classrooms while it is being reviewed and reportedly remains in storage. Books in the collection include Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard, Dim Sum for Everyone by Grace Lin, and Pink Is For Boys by Robb Perlman, among other titles designed to make classroom libraries more diverse and inclusive.

As the school year progressed, those demanding book removals increasingly turned their attention to books that depict LGBTQ+ individuals or touch on LGBTQ+ identities, as well as books they claimed featured “sexual” content, including titles on sexual and reproductive health and sex education. These trends were already identified in PEN America’s first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022) report; however, from April to June, there was an acute focus on these topics. This dovetailed with the passage in late March of the “Parental Rights in Education” law in Florida—also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law—and the introduction of similar legislation in other states, as well as a range of efforts to censor discussion of LGBTQ+ identities in schools, in Maryland, Missouri, Texas, and beyond. From April to June 2022, a third of all book bans recorded in the Index feature LGBTQ+ identities (92 bans). Over the same short period, nearly two thirds of all banned books in the Index touch on topics related to sexual content, such as teen pregnancy, sexual assault, abortion, sexual health, and puberty (161 bans).

These subject areas have long been the targets of censorship and been controversial from the perspective of age appropriateness, with standards and approaches varying from community to community about what is seen as the right age level for such material, as well as the degree to which these topics should be addressed in school as opposed to in the home. As book banning has resurged, some individuals and groups have sought to reignite debate about sexual content in books, and sexual education in schools generally. While debate on these issues recurs, wholesale bans on books deny young people the opportunity to learn, to get answers to pressing questions, and to obtain crucial information. At the same time, the efforts to target books containing LGBTQ+ characters or themes are frequently drawing on long-standing, denigrating stereotypes that suggest LGBTQ+ content is inherently sexual or pornographic.

The most banned book titles include the groundbreaking work of Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, along with best-selling books that have inspired feature films, television series, and a Broadway show. The list includes books that have been targeted for their LGBTQ+ content, their content related to race and racism, or their sexual content—or all three.

These groups have employed a range of common tactics to advance book banning in public schools. Most of these tactics, it should be emphasized, are tactics that many advocacy and community organizing groups employ to a wide range of ends. Citizens are free to organize and advocate; these liberties are protected under the First Amendment’s safeguards for freedom of association. PEN America’s concern is not with the use of such standard organizing and mobilization tactics but rather with the end goal of restricting or banning books. That said, in some cases, members of these groups have also crossed a line, using online harassment or filing criminal complaints to pressure local officials and educators.

One common trend is that many of these groups circulate to their audiences lists of books to target. PEN America saw dozens of lists that circulated online during the 2021–22 school year, and these also occasionally morphed or grew in the process of being shared among groups.

Some groups appear to feed off work to promote diverse books, contorting those efforts to further their own censorious ends. They have inverted the purpose of lists compiled for teachers and librarians interested in introducing a more diverse set of reading materials into the classroom or library. For example, one group, the Idaho Freedom Foundation, referenced multiple lists celebrating books about equity, inclusion, and human rights under the header “Federal Agencies Are Sexualizing Idaho Libraries,” accused the federal government of using “taxpayer dollars to promote a pernicious ideology to young children,” and called on the Idaho legislature to reject federal funds for libraries. Another group, the Michigan Liberty Leaders, took an image of books from the Welcoming Schools bullying prevention program created by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation—including books designed to support LGBTQ+ students—and added alarmist language about the books being in schools.

In another example, the list of books created by the FLCA in their “Porn in Schools” report originated from the website Christian Patriot Daily, which said it received its list from a graduate student in early childhood development promoting LGBTQ+ resources for caregivers. This list has in turn appeared to spread across state lines. In March 2022, in Cherokee County School District in Georgia, a parent presented a list of 225 book challenges. In that list, 41 titles were not only identical to those in the 2021 FLCA report, but they were in the same order, with the same typos found in the original list. The same list also appears in a database of books on the website of Forest Hills Parents United, based in Michigan.

The books on these lists are often framed as dangerous or harmful, and the lists have been used to quicken the pace of book banning, often in violation of or with disregard for established, neutral processes, with demands that all books on such lists be removed from schools immediately.

Beyond the school book bans documented in the Index and the efforts of various parties to see their implementation and enforcement, the past year has also seen attempts to change laws and school district policies in ways that make censorious challenges easier to file and impose. Even where such laws and policy changes have not been enacted, their chilling effect has been broadly felt.

The book-banning movement has operated in conjunction with legislative efforts to pass educational gag orders, all as part of what PEN America has referred to as the “ed scare”—a campaign to censor free expression in education. While the effort to constrain teachers has primarily progressed in state legislatures—as PEN America has documented, most recently in our August 2022 report America’s Censored Classrooms—and the effort to ban books has erupted mostly within local school districts, the two have increasingly merged, with some state legislators proposing or supporting bills that directly impact the selection and removal of books in school classrooms and libraries.

The unrelenting wave of challenges to the inclusion of certain books in school libraries—whether promulgated at the urging of an individual community member, grassroots organization, or government official—has spurred another phenomenon: preemptive book banning. In April, May, and June 2022, PEN America tracked several cases where school administrators have banned books in the absence of any challenge in their own district, seemingly in a preemptive response to potential bills, threats from state officials, or challenges in other districts.

The most significant ban of this type occurred in Collierville, Tennessee, where a school district removed 327 books from shelves in anticipation of a state law that ultimately did not pass. Administrators sorted the books into tiers based on how much the books focus on LGBTQ+ characters or story lines; tier 3, for instance, reflected that “the main character of the book is part of the LGBTQ community, and their sexual identity forms a key component of the plot. The book may contain suggestive language and/or implied sexual interactions.” If a book reached tier 5, according to the sorting guidelines, “the books are being pulled.”

Other preemptive bans were responses to actions at the state level or in neighboring districts. For example, according to Texas media reports, bans in Katy ISD, Clear Creek ISD, and Cypress-Fairbanks ISD were the result of administrators responding either to what was happening in other districts or to an 850-book list compiled and circulated to education officials by Texas state representative Matt Krause.

Finally, PEN America has tracked other instances of books included in banned book displays, or other disputed materials, being quietly removed to avoid controversy. Books are also being labeled or marked in some way as “inappropriate” both in online catalogs and on physical titles themselves. In the Collier County School District in Florida, for instance, warning labels were attached to a group of more than 100 books that disproportionately included stories featuring LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color. While these cases are not included in the Index because they do not meet PEN America’s definition of school book bans, these types of actions could have a chilling effect—applying a stigma to the books in question and the topics they cover—and they merit further study.

While several stories of preemptive and silent book bans have made it into the news or to the attention of PEN America, it is clear that mounting censorship and the punitive approach being taken to the enforcement of book bans is having wide ripple effects. The Supreme Court has sharply restricted viewpoint- and subject-matter-based restrictions on speech precisely because in addition to rendering certain ideas, stories, and opinions off-limits, such measures cast a wider chilling effect on expression. Given the rapid spread of book bans across the country, it seems inevitable that the resulting climate of caution and fear will result in a reluctance among teachers, administrators, and librarians to take risks that could affect their own employment, their budgets, their reputations, and even their personal safety. Emerging data, like a recent survey of school librarians by the School Library Journal in which 97% said they “always,” “often,” or “sometimes” weigh how controversial subject matter might be when deciding on book purchases is pointing clearly to these alarming trends.

Beyond formal book bans, there have also been efforts to keep books out of the hands of children even if they remain in circulation. One prominent example of such activity was “Hide the Pride,” an initiative of CatholicVote.org in June 2022. CatholicVote encouraged members to check out books from the Pride 2022 displays in children’s sections of public libraries and to take pictures of the empty shelves. Although the group instructed participants to “return your library books on time” and to follow the “letter of the law, so to speak,” Hide the Pride was an attempt to remove library materials from availability and to limit students’ access to LGBTQ+-affirming books. In the same month, there were efforts to ban displays of LGBTQ+ materials entirely in some public libraries, such as in Smithtown, New York, and Lafayette Parish, Louisiana. The latter resulted in an effort to terminate a librarian for allegedly violating the prohibition.

The unprecedented flood of book bans in the 2021–22 school year reflects the increasing organization of groups involved in advocating for such bans, the increased involvement of state officials in book-banning debates, and the introduction of new laws and policies. More often than not, current challenges to books originate not from concerned parents acting individually but from political and advocacy groups working in concert to achieve the goal of limiting what books students can access and read in public schools.

As noted previously, the resulting harm is widespread, affecting pedagogy and intellectual freedom and placing limits on the professional autonomy of school librarians and teachers. The repercussions extend further, however, to the well-being of the students affected by these bans. Children deserve to see themselves in books, and they deserve access to a diversity of stories and perspectives that help them understand and navigate the world around them. Public schools that ban books reflecting diverse identities risk creating an environment in which students feel excluded, with potentially profound effects on how students learn and become informed citizens in a pluralistic and diverse society.

Book challenges impede free expression rights, which must be the bedrock of public schools in an open, inclusive, and democratic society. These bans pose a dangerous precedent to those in and out of schools, intersecting with other movements to block or curtail the advances in civil rights for historically marginalized people.

Against the backdrop of other efforts to roll back civil liberties and erode democratic norms, the dynamics surrounding school book bans are a canary in the coal mine for the future of American democracy, public education, and free expression. We should heed this warning.

This report was written by Jonathan Friedman, director, Free Expression and Education Programs, based on research and analysis by Tasslyn Magnusson, Ph.D., and Sabrina Baeta. The report was reviewed and edited by Nadine Farid Johnson, managing director of PEN America Washington and Free Expression Programs; Summer Lopez, chief program officer, Free Expression; and Jeremy C. Young, senior manager, Free Expression and Education, who also helped supervise the production process. Lisa Tolin provided editorial support, and Dominique Baeta provided research assistance. Finally, we extend thanks to the many authors, teachers, librarians, parents, students, and citizens who are fighting book bans, speaking at school board meetings, and bringing attention to these issues, many of whom inspired and informed this report.